Dispute resolution boards

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

This article introduces the concept of Dispute Resolution Boards (sometimes referred to as Dispute Review Boards) and Dispute Adjudication Boards, how they are established, and how they operate in practice.

Dispute Resolution Boards (DRB) administer a type of dispute resolution without any specific description. DRBs have evolved over time and can be formulated in a number of different ways. The procedure is based on contract rather than statute, and the parties to a contract are able to agree to a formulation that suits their particular project. A few standard contracts have DRBs as part of their terms, of which the most prominent are the FIDIC contracts and the World Bank (Procurement of Works) contract.

It seems to be accepted that the first DRB was set up in 1975 for the Eisenhower Tunnel in Colorado, USA. This followed the first tunnel bore that had been constructed between 1968 and 1973. The project was a disaster, in that it overran in both time and money, with many disputes arising. When it came to the second bore, notice was taken of a study entitled Better Contracting for Underground Construction published in 1974.

This report highlighted the incidence of claims, disputes and litigation together with the additional costs that inevitably flowed from those claims. Based on the report, it was decided that the second bore of the Eisenhower Tunnel contract would incorporate a DRB. The hope was that the high level of cost overrun and disputes experienced on the first bore could be minimised by use of the DRB.

It was a tremendous success. Although disputes did arise, they were dealt with very swiftly and effectively by the DRB, to the extent that there was no ensuing litigation.

The DRB was set up in the form of a Review Board rather than an Adjudication Board, and their findings were recommendations rather than binding decisions. The losing party was not obliged to follow the recommendation. The dispute could thereafter be taken to a higher authority where a binding decision could be made.

The use of DRBs on major projects confined to the USA increased. The World Bank took note and in 1980 decided that a project known as the El Cajon Dam and Hydro Scheme in Honduras was a suitable candidate for a DRB. The World Bank was a major funder of the project with a Honduran owner (who had not undertaken such a large project previously), an Italian contractor and a Swiss engineer. It is easy to see how misunderstandings could occur with such a diverse cultural mix, and the World Bank insisted that in order to obtain funding a DRB should be formed to deal with issues on the project as they arose.

That project was also a success. DRBs were launched into the international construction arena and broke out of their American birthplace.

As DRBs became more commonly used on international construction projects, various institutions began to take more notice of them. In 1990, the World Bank published its Procurement of Works, which for the first time incorporated a procedure for DRBs in the form of a modified FIDIC contract. This procedure incorporated non-binding recommendations.

FIDIC itself followed this with the publication of an amendment to its form in which the concept of Dispute Adjudication Boards (DABs) was introduced. These differed from the Dispute Review Boards in that a temporarily binding decision was introduced, very much in the same way as domestic adjudication in the United Kingdom.

In 2000, the World Bank revised its DRB procedure, introducing the idea of interim binding recommendations, displacing the engineer from a former role in which decisions on disputes were required. In the same year, FIDIC published a suite of contracts incorporating DABs, whereby interim binding decisions in respect of disputes could be made. The costs of the DAB are shared equally between the parties.

In 2003, the European Union published a directive that prescribed the use of these FIDIC contracts incorporating DABs on all construction projects that receive EEC funding.

The ICC rules allow for a choice of non-binding recommendations, adjudication decisions and a combined approach that allows the DAB to act as an adjudication board at the request of one party, with the proviso that if the other party objects, the board will decide in what capacity it is to hear the dispute.

To date, well over 1,000 construction and engineering projects worldwide have used DRBs with a total construction cost of some US$100 billion. The success of DRBs is illustrated by the fact that fewer than 3% of disputes that arose became the subject of an arbitration or litigation.

DRBs are most suited to large, complex construction and engineering projects on an international scale, although more domestic projects are incorporating these ideals; for example the Channel Tunnel Rail Link had a DRB. This was a huge project. Two panels were appointed, one to deal with the technical issues (three engineers) and the other to deal with disputes concerning the financial provisions of the project.

[edit] Composition of a dispute resolution board

The DRB is a creature of the contract. Usually, the contract will provide for three members, two technical and one legal, usually the chairman. This formulation allows for technical disputes to be fully understood and resolved without the need for external advice, and similarly disputes involving or including legal issues being capable of resolution without external advice. The idea is for the board to be able to deal with any dispute that arises.

Clearly, each board member needs to be a respected member of their own profession, with qualifications and experience to match the project in hand.

Essentially, the DRB can be likened to a project management tool that is used to ensure that the project remains on track, influencing the parties to the project to carry out their contractual obligations properly.

The three-member DRB will visit the project regularly and deal with any difficulties that have arisen. Occasionally, it will have to convene outside of its regular visits if a particular dispute requires it. The advantage to the parties is that the DRB gains an ongoing knowledge of the project as the members are exposed to the facts of any emerging disputes at a very early stage.

The operational philosophy behind a DRB is to provide interim solutions that are in tune with the interests of the project in a quick and effective manner. It is a process that is intended to find solutions to problems rather than form an adversarial forum. DRBs are designed to keep the parties working constructively together while finding solutions to problems as they occur, rather than allowing those problems to escalate in an ultimately destructive manner.

[edit] Selection of the dispute resolution board

The success of a DRB is dependent not only on the procedure that has been put in place but also on the members of the DRB itself. Of course, the importance of the willingness of the parties themselves to work constructively with the DRB and make commercial compromises should not be forgotten.

The selection of the members of the DRB is crucially important to the parties, and therefore an appointment procedure is required within rules set out in the contract. Normally, each party nominates one member and those members then choose a third member as chairman. This allows each party to have the comfort of a board member who is in tune with their thinking, while the chairman is independent of both. In default of agreement between the two members, a nominating body should independently select and appoint the chairman. Again, that procedure must be part of the written contract.

When appointing members for the DRB it is useful to consider their experience not only in construction and engineering but also in contract management and the applicable law of the contract. A mix of all these elements may be required in varying degrees. Ideally the board should not consist entirely of like-minded individuals but be a combination, such as two construction or engineering professionals and a lawyer versed in construction and engineering law as well as the law of the contract.

[edit] Dispute resolution board procedure

Once the members of the DRB have been appointed, the procedure should allow for regular visits to site, including time to deal with any differences that have arisen. This should also allow for less formal ‘opinions’ to be given by the DRB in respect of what might be potential disputes.

The use of the DRB for informal discussions between the parties (together or separately), with or without the engineer should be encouraged. Where an opinion has been sought, the DRB may respond in writing (or orally if followed up in writing), and by that informal process the potential dispute may be avoided. If not, the formal dispute procedure requiring a written recommendation by the DRB, or a written reasoned decision by the DAB, will commence.

The formal procedure usually involves the dissatisfied party issuing a written notice containing details of the dispute to the other party and to the DRB. That notice may be dependent on timing should the contract so indicate. For example, FIDIC only allows 28 days after the engineer’s decision in which to issue a notice.

Having issued the notice, the claimant has to prepare a position statement in which they set out their legal and factual arguments, supported by evidence. On receipt, the defendant will prepare their position statement responding to the claimant’s narrative, setting out their arguments and the evidence relied upon.

Having received the two position statements, the DRB will consider the matters raised. If necessary the members of the DRB will meet before the hearing to discuss procedural or substantive matters.

The DRB will prepare a list of questions or further documents required so that the hearing will be able to deal fully with all matters arising. The hearing will normally be held within 30 days (15 days in the ICC rules) of the defence being served, usually on or near the project. The length of the hearing is dependent on the complexity of the matters before the DRB, but is very unlikely to exceed one week. In fact, most hearings do not exceed two or three days.

The hearing follows the usual course: a submission by the claimant, a submission by way of reply from the defendant, with perhaps questions and points of clarification raised by the DRB. If necessary the engineer will be allowed to make submissions or answer questions.

After the hearing is brought to a close, the DRB will continue with its deliberations and a draft recommendation or adjudication decision will be prepared. This is necessary, as the three-man board will thereafter return home to prepare their individual reports for later discussion and to finalise their recommendation or adjudication decision.

Time is always of the essence in making a recommendation or decision, as the parties will be continuing with the works, and the decision needs to be known sooner rather than later. In any event, the rules should have a time limit for the board to make its decision, subject to the claimant being able to grant the DRB a limited extension to that time if special circumstances arise which prevent a recommendation or decision being made in the prescribed time. The recommendation or decision will be produced by way of a written report.

Where the Board provides recommendations, these can be without sanction or a time limit. To provide certainty, a time limit can be prescribed for any written objection to be made by either party. If no objection is raised, then the recommendation can become binding on the parties. In any event, the recommendation or decision should be stated in the contract to be acted upon immediately it is published.

[edit] Procedural fairness

As with any dispute resolution process, to be effective the decision-making process should be seen to be fair. Natural justice has been the source of much comment and legal analysis, especially in respect of statutory adjudication in the UK.

Dispute Review Boards are not a creature of statute, they are a creature of the contract. In this respect, they seem to have more in common with expert determination than arbitration or adjudication. Expert determination has no remedies for procedural irregularity and cannot be set aside under those circumstances, unlike arbitration. An expert may investigate and come to their conclusions without reference to the parties. Their power is absolute, as it derives from the contract.

Unless the contract states otherwise, the expert cannot be challenged if the parties have agreed to accept the determination as being final. Similarly, the only challenges to the DRB’s jurisdiction are those set out in the contract. If the parties wish the DRB’s decision to be final and binding, this should be reflected in the contract.

The courts may decide to follow the lead of adjudication practice in the UK and scrutinise DRB decisions for procedural fairness. An example of the courts refusing to accede to a DRB process for lack of procedural fairness can be found in the case of Sehulster Tunnels and Pre-Con (Joint Venture) v Traylor Brothers Inc and Obayashi Corporation (Joint Venture) (12 September 2003) Court of Appeals of California, Fourth Appellate District.

In this case, a DRB had been set up on a large outfall system taking treated waste out by tunnel into the ocean in Southern San Diego County, California. The contract was worth some US$90 million. The DRB was to be by the appointment of the employer, the city of San Diego, and the contractor, Traylor Brothers Inc and Obayashi Corporation, a joint venture. The subcontract for the manufacture of the concrete rings forming the tunnel lining was with Sehulster Tunnels and Pre-Con, also a joint venture.

The subcontract reflected the DRB procedure found in the main contract, but importantly did not allow Sehulster to appoint one of the members to the DRB. When a dispute arose, the contractor and the employer insisted that the DRB be used but refused Sehulster’s request to appoint a member of the DRB. Sehulster therefore ignored the DRB provisions and litigated in the courts.

The court at first instance found in Sehulster’s favour. The matter went further. It was argued at the Court of Appeal that as the subcontract incorporated the DRB by reference, and in order for Sehulster’s claim to proceed, the DRB mechanism had to be used. In response, Sehulster argued that the first instance decision should be upheld and that the DRB was presumptively biased against Sehulster, as Sehulster was unable to appoint a member to the Board. Sehulster further argued that the condition precedent for the DRB contained within the subcontract could not be enforced and Sehulster had every right to litigate in the courts.

The Court of Appeal agreed with Sehulster, saying:

- ‘Sehulster in this context should not be required to pursue a charade characterised as meaningful ADR. Secondly, although the DRB’s recommendation is non-binding, it is not without influence because the Prime Contract provides for its admissibility into evidence in any later dispute resolution or legal proceeding. Finally, it does not follow that because the DRB process does not constitute binding arbitration, Graham’s notions [Graham v Scissor-Tail Inc (1981) 28 Cal.3d 807, 817-819] regarding presumptive bias are inapplicable in this context, therefore permitting enforcement of the condition precedent of pursuing the DRB process to preclude resolution of Sehulster’s claim by litigation…

- ‘… contractual ADR must operate within minimum levels of integrity to pass judicial muster, the court held that the minimum levels of integrity had not been achieved …’.

This case also makes observations in respect of DRBs in general, and these are worth repeating here:

- ‘The DRB process constitutes a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) most commonly employed in tunnelling and other large, complex, heavy construction projects. First utilised in the mid-1970s, it has proven particularly advantageous in contracts' performance of which will take a long period of time, and in which disputes are inevitable and multiple instalment payments are contractually required on completion of performance milestones or components of the work.

- ‘Generally, the DRB serves as a safety net to resolve problems or matters about which reasonable people could differ before they harm the business relationship between the parties and result in acrimonious litigation. It is composed of three experts, selected by the parties at the beginning of the project, who become familiar with it, monitor its progress and are available to provide advisory decisions on short notice concerning disputes the parties are unable to resolve themselves. The availability of the DRB and its familiarity with the project enable prompt resolution of disputes, which furthers the goal of preserving cooperative relationships between the contracting parties.

- ‘The DRB process resembles the arbitration process with several significant differences. First, the DRB is a standing tribunal contractually required to be formed and in place within a few months after the owner gives the contractor notice to proceed. Second, the process envisions: an introductory/orientation meeting for the DRB members to become acquainted with the owner, the contractor, and their key personnel; a brief history of the project, including significant potential technical, environmental, political or social issues that might arise from it; and the scope and anticipated schedule of construction. Third, the DRB meets regularly throughout construction of the project. The frequency of meetings is dictated by the project’s size, complexity, schedule and number of claims or problems. Fourth, unlike standing arbitrators who make immediately binding decisions, the DRB issues advisory opinions or non-binding recommendations.’

As exemplified here, the DRB is a creature of contract designed to provide recommendations to resolve particular disputes. Because the DRB’s recommendations are non-binding and may be rejected by either the owner or the contractor, it is important for the credibility of the DRB that the parties perceive its members as generally qualified and neutral.

The DRB process is designed to promote the parties’ confidence in it by providing their equal involvement in the selection of the individual DRB members who have experience in that type of construction, contract interpretation and dispute resolution.

[edit] Enforcement

The recommendation or decision of a DRB is a contractual matter, and therefore any enforcement, will be seen in the light of a breach of contract. Enforcement will usually be a matter of the jurisdiction within which the DRB is operating. In England and Wales, the courts will not allow a party to avoid the DRB machinery, and summary judgement will recognise any express contractual provisions.

[edit] Conclusion

Those that have been involved with DRBs generally agree that on large projects they assist the parties to resolve their differences, enabling the project to be completed with much less chance of an acrimonious dispute developing into a major arbitration or litigation.

When a difference does become a dispute, it is dealt with quickly and so prevents the matter getting out of hand. The parties remain focused on the project rather than the dispute.

As to the members of the DRB, they are familiar with the progress and technical issues associated with the project; when a recommendation or decision is needed, it is made on the basis of the submissions but also on the knowledge that has been built up by the DRB.

DRBs provide a confidential forum in which difficulties or disputes can be resolved. They are not set up to apportion blame but rather to resolve issues that have arisen in a way that allows the project to proceed smoothly.

[edit] About this article

This article was created by the University College of Estate Management (UCEM) in December 2012.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Adjudication.

- Alternative dispute resolution.

- Arbitration.

- Breach of contract.

- Causes of construction disputes.

- Construction Industry Model Arbitration Rules CIMAR.

- Contract claims.

- Dispute avoidance.

- Dispute resolution.

- Dispute resolution procedure.

- Expert determination.

- How does arbitration work?

- Legal action.

- Mediation.

- Pay now argue later.

- Pendulum arbitration.

- The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act.

- The role of the mediator.

- The Scheme for Construction Contracts.

[edit] External references

- Sliwinski R A (Barrister, Attorney – New York) (2004) ‘Dispute Resolution Boards’, Occasional Paper.

- Groton J P, Rubin R A and Quintas B (2001) ‘A Comparison of Dispute Review Boards and Adjudication’, The International Construction Law Review pp.275–291.

- Knight P (2001) Alternative Dispute Resolution 3:720–3:723. The Rutter Group.

- Henn (1999) ‘Dispute Review Boards: ADR Form for the Construction Industry’, 28 Colo. Law 51–52.

Featured articles and news

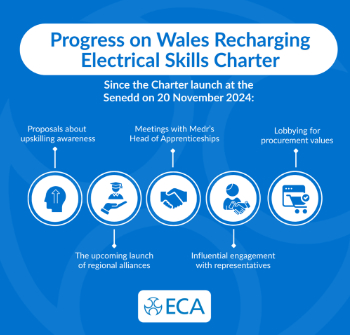

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.